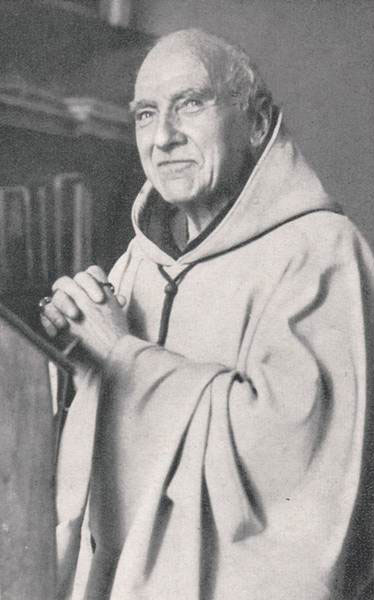

REV. DOM VITALIS LEHODEY

ON MENTAL PRAYER

THE FIVE FIRST SATURDAYS IS A DEVOTION NEEDED NOW MORE THAN EVER! FIND OUT MORE HERE

THE SAINT MICHAEL PRAYER AND THE ROSARY

ARE ALSO POWERFUL PRAYERS TO HELP US THROUGH THESE VERY TURBULENT TIMES!

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED! DELIVERANCE PRAYERS,

A BOOK FROM SENSUS TRADITIONIS PRESS

(A GREAT PUBLISHER HELPING US FIGHT OUR MANY SPIRITUAL BATTLES NOWADAYS)!

CHECK OUT OUR PODCAST PAGE AND OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL FOR INSPIRING CONTENT

We are pleased to print below this selection from The Ways of Mental Prayer, a great authoritative treatise on the subject of Mental Prayer by the late Dom. Vitals Lehody (1857-1948; pictured above) who was ordained a priest in the town of Coutances in France in 1880 and elected abbot of Bricebeq, also in that country, some fifteen years later.

This book, along with his other well-known work Holy Abandonment, has stood the test of time and, happily, both are still in print. The Ways of Mental Prayer covers all aspects of this subject, from its basics, as outlined in part below, all the way up through its more mystical, contemplative elements.

(These are for those, mainly but by no means exclusively, religious, for whom intimate conversation with God has become so natural and spontaneous that they can go past some of the formative steps outlined below.)

This book garnered recommendations from such preeminent figures in our faith as Fr. Reginald Garrigou-LaGrange, once called last century's "greatest authority on mystical theology" and Pope Saint Pius X, who called The Ways of Mental Prayer "a work very useful, not only to religious, but to all who, in any walk of life, are striving after Christian perfection."

We start here with Rev. Lehodey's introduction to this chapter titled "On Ordinary Mental Prayer", in which he touches on the various types of mental prayer.

Rest assured, however, that he means nothing pejorative in its title. "Ordinary" mental prayer can bring about some extraordinary results, both as a stepping stone to higher forms of meditation and contemplation, and for those insights you may garner in your time with God that bring you closer to Him!

Keep in mind, always, that the methods in mental prayer described below are meant as suggestions, as "training wheels" are on a bicycle, with the important diffrerence that you can use them as long as you find them helpful, with no time limit.

Don't ever feel like you need to give up on mental prayer because you're "doing it wrong"! The only "wrong" way to do mental prayer is not to do it at all, or to give up on it quickly if you feel you're not "getting anything out of it."

If you give up because of dryness or distractions (which all the saints experienced at one time or another) you might very well miss out on other opportunities to experience God's love and wisdom in ways you never imagined!

As Fr. Lehodey himself writes below "Prayer is more the work of the heart than of the head; it should, therefore, be simple, affective, and sincere. Let not the mind, then, weary itself in seeking for beautiful thoughts and sonorous phrases; we meditate not to prepare a finished sermon, nor to address God with fine rhetoric, but to nourish our soul with reflections which may enlighten and move us, and excite holy and generous resolutions; we make these reflections for ourselves alone, let them, then, be simple as well as pious."

We suggest reading this page slowly, thoughtfully, and prayerfully. We have highlighted some key parts of this chapter here, for our readers' convenience, yet the whole section could be highlighted!

We hope you find it helpful in drawing closer to our Lord and advancing in holiness as a citizen-in-training for Eternal Life with Him and all the saints in heaven (including yourself!) See also our article on Mental Prayer for more tips and information.

ON ORDINARY MENTAL PRAYER

ORDINARY mental prayer includes meditation and its equivalents, affective prayer, and the prayer of simplicity. These resemble each other inasmuch as they are in no way passive; the supernatural is latent in them.They differ in their ways of working.

In meditation, considerations occupy more time, whereas they become fewer and shorter in the prayer of affections; and, in the prayer of simplicity, the work of the intellect is reduced to almost a simple look at God or the things of God.

The affections gaining all the ground lost by the considerations, follow an opposite course. In proportion as progress is made, they occupy more and more time, and end by occupying even the whole time of prayer.

But, like the work of the understanding, that of the will also continues to become more and more simple; and the soul, which in the commencement had need of quite an equipment of considerations and verbose and complex affections, advances gradually towards a kind of active prayer which is little more than a loving attention to God, and an affectionate conversation with Him. We shall treat somewhat more at length of meditation, which, being the prayer of beginners, has a greater need of method and rules.

CHAPTER I

PRAYER OF MEDlTATION-COMPENDlUM OF THE METHOD

I. GENERAL IDEA

THE prayer of meditation is a mental prayer composed of considerations, affections, petitions, and resolutions.

It is called simply mental prayer, because it is the portion of a very great number, and the first stage in the ways of mental prayer. It is called also meditation, discursive prayer, prayer of reasoning, on account of the important part which considerations have in it, and to indicate that the mind proceeds therein not by a simple look, but by the roundabout ways of reasoning.

Let us note, first, that all the parts of mental prayer or meditation ought to converge to one single end, the destruction of a vice, the acquisition of a virtue, or some spiritual practice which may serve as a means to this. We should occupy ourselves chiefly about our predominant sin or vice, about some fundamental virtue, or some more essential practice. Our subject, our considerations, our affections and petitions, should be chosen and regulated in view of this one object.

Let each one then accommodate his meditation to the state of his soul, the attractions of divine grace, and his own present needs. A sinner, and even the greatest of sinners, can make his meditation, but let him treat with God of his sad state in order to become converted; the man of bad will can and should pray, but let him converse with God precisely about his bad will in order to be delivered from it.

The tepid soul should pray in order to abandon venial sin; the fervent should pray the prayer of the fervent, in order to love more and to persevere; the soul buffeted by trials the prayer of the tried soul that humbles and subjects itself under the hand of God in order to recover peace.

This accommodating of our prayer to our present state renders it profitable and efficacious, sweet and easy; what can be more consoling and more easy than to converse with Our Lord about what we are and what we are at present experiencing?

On the other hand, if our prayer is not accommodated to the present state of our soul, does it not, by the very fact, lose the greater part of its attraction and utility?

It is better, at least for beginners, to prepare the morning meditation the evening before during the last free time. Let them choose a subject, which they may divide into several points, each containing sufficient doctrine to enable them to elicit affections and to draw practical conclusions; let them foresee in each point the reflections to be made, the affections and resolutions to be drawn from it.

Yet the same one resolution may last them for a considerable time. It is good to fall asleep with these thoughts, and to run over them again on awaking. ln this way, when the time of prayer comes, the mind will already be full of them and the will on the alert.

We may add, that the most effective disposition for prayer is a hunger and thirst after holiness, a lively desire to profit by our prayer in order to advance in perfection. “Without this desire, the evening preparation will be languid, the morning waking without ardour, the prayer almost always fruitless."

"This desire to belong entirely to God and to advance in His love is a continual prayer," says St. Bernard. We ought always to be on the watch not to let it grow cold, but ever to inflame it more and more. It is the very soul of prayer, as indeed it is also of the whole spiritual life.

Thus the soul, prepared remotely by the fourfold purity already described, and proximately by the choice of a subject and a spiritual hunger, will secure the success of her prayer. But how is she to employ herself therein?

We shall explain further on, with abundance of detail, the essential acts of meditation, as well as some others which are rather optional. It will be a plentifully-served table, sufficient we hope for the various tastes and needs, and whence each one can pick and choose if he does not want to take all.

But, for greater clearness, we shall begin by giving an abridgement of the method, which will include only the necessary acts; it will be short, simple, easy, yet full. We shall add a couple of brief explanations to convey a better understanding of the mechanism of the method; the details will come afterwards.

II. COMPENDIUM OF THE METHOD

Meditation comprises three parts, very unequal in importance and duration; the preparation, the body of the meditation, and the conclusion.

I. The preparation, or entrance into conversation, requires a few minutes at most. It essentially consists in placing oneself in God's presence, Who is looking upon us and listening to us. It is becoming to begin our conversation with a God so great and so holy, by acts of profound adoration of His Majesty, of true humility at the sight of our nothingness, and of sincere contrition for our sins.

We then beg the grace of God, without which we cannot pray. If the soul is already recollected; for instance, when we have just ended another pious exercise (as generally happens in the case of the meditations prescribed by our rule), the preparation is sufficiently made by the very fact, and we can enter at once into the body of the prayer, unless we prefer to employ a moment in reanimating our faith in the presence of God, and in asking His grace in order to pray well.

II. The body of the meditation is the chief part of this exercise, and it occupies almost its whole time It consists of four acts, which form the essence of meditation; these are considerations, affections, petitions, and resolutions.

1) [Considerations:] We reflect on a given subject, we turn it over in our mind again and again on every side in order to grasp it well and to become thoroughly impressed by it; we draw the conclusions and make the practical applications which flow from it.

This is the meditation properly so called. It is not a mere speculative study, stopping short at the knowledge of principle; its remote end is to strengthen our convictions in the course of time, and its immediate end is to call forth affections, petitions, and resolutions.

We then examine ourselves with regard to the subject on which we are meditating, to see whether our conduct is conformed to it, in what we fail, and what remedies we are to employ.

This work of the mind is not yet prayer, it is only introductory. Along with the preparation it ought not generally to occupy more than about half the time of the whole exercise; the other half is reserved for acts of the will which constitute the prayer proper; these are affections, petitions, and resolutions.

2) Certain affections arise of their own accord from the reflections we have been just making; thus, hell arouses repentance and aversion from sin; heaven calls forth the contempt of this world and the thirst after eternal goods; Our Saviour's Passion excites love, gratitude, confidence, contrition, humility, &c.

The examination of ourselves gives rise to regret for the past, confusion for the present, strong resolutions for the future. We may add at will many other affections, selected preferably from amongst those that are fundamental. We shall mention in their own place those that are most recommended.

3) Petition is an important point, and we should dwell upon it for a long time with faith and confidence, humility and perseverance, while, at the same time, urging the reasons likely to move Our Lord, and invoking the aid of the Holy Virgin and the saints.

We should first ask those graces which the subject of our prayer suggests, and then it is well to add petitions for divine love, final perseverance, the welfare of the Church, our country, our order, our house, our relations, sinners, souls in purgatory, &c.

4) Resolutions end the body of the meditation. One single resolution, precise and thoroughly practical, suffices, provided only that it be kept.

III. The conclusion consists in thanking God for the graces He has granted us during our prayer, in asking pardon for our faults and negligences. Finally, we may again recommend to Him our resolution, the coming day, our life, and our death.

To sum up then, after having placed ourselves in the Divine presence, we reflect upon a pious subject, examine ourselves, form suitable affections and petitions, make a resolution, and, having thanked God, we retire. [Italics here ours]

III. TWO SHORT EXPLANATIONS

Nothing can be simpler or more natural than the mechanism and working of this method.

I. Prayer is an audience with God.

No human motive should lead us to pray: neither routine, nor the habit of doing as others do, nor a thirst for spiritual consolations. No, we should go to prayer to render homage to God. It is not, however, a common-place visit of propriety, nor a conversation without any precise object; we want to obtain from Him some definite spiritual good, such or such progress in the uprooting of some vice, in the acquisition of some virtue. We have, therefore, a purpose upon which we are bent, and all our considerations, affections, petitions, and resolutions should combine for its attainment.

God is there, surrounding us and penetrating us; but we were not, perhaps, thinking of this. We must, therefore, withdraw our powers from the things of earth, gather them together, and fix them upon God; thus it is we place ourselves in His presence.

Naturally, we approach Him by saluting Him with a profound and humble act of adoration. In presence of so much greatness and holiness, the soul perceives herself to be little and miserable; she humbles herself, purifies herself by an act of sorrow; apologises for daring to approach a being of so lofty a majesty. Powerless to pray as she should, she represents her incapacity to God, and begs the Holy Ghost to help her to pray well.

The preludes ought to be short, in order to come quickly to the proper object of the interview-that is, to the body of the meditation.

The work of the considerations is to show how desirable the spiritual good we have in view is, and that of the examination to show how much we stand in need of it.

They may be made as an internal soliloquy, a solitary meditation, in which we labor to convince ourselves in order to excite, along with repentance and confusion, ardent desires, fervent petitions, and strong resolutions.

It is more becoming, however, as we are in God's presence, not to be so intent on our own reflections as to neglect Him, but to make our considerations as though speaking with Him, and to mingle with them pious affections. In this way, our prayer will be a devout pleading-, wherein the soul, whilst urging its reasons before God, becomes inflamed with a love for virtue, a horror of vice, understands the need it has of prayer, and begs with all the ardour of conviction the grace it wants, whilst at the same time it labours to persuade God, to touch His heart, to open his hand, by means of the most powerful motives it can think of.

We came to ask a definite spiritual favour, and we should urge this request in a pressing manner; but we should not forget that God, who is liberal almost to excess, loves to find empty vessels, into which He may pour His gifts, to meet with hands opening wide to receive them; and the more he is asked for the better pleased He is, such joy does it give Him to bestow good gifts on His children! We should profit, then, of this audience to expose our other needs, to ask for all sorts of favours, general and particular.

God has given His grace, we must now cooperate with it. Hence we form a resolution which will make that grace bear fruit.

The audience ended, we thank God for His goodness, apologise for our own awkwardness, ask a final blessing, and withdraw.

II. According to the beautiful doctrine of M. Olier [a beloved 17th century French Catholic priest who founded the Society of the Priests of Saint Suplice], mental prayer is a communion with the internal dispositions of Our Lord.

The well-beloved Master is, at the same time, both the God who has a right to our homage and the model whom we should imitate. It is impossible to please the Father without resembling the Son; and equally impossible to resemble the Son without pleasing the Father. For a religious, who is seeking God and tending to perfection, all may be reduced to his adopting the interior sentiments of Our Lord, following His teaching and copying His example.

A soul is perfect when it is an exact copy of the divine model. Nothing, then, is so important as to keep Him continually before our eyes in order to contemplate Him, in our hearts in order to love Him, in our hands in order to imitate Him. This is the whole economy of mental prayer, according to M. Olier.

If I want to meditate upon humility, my object in the adoration will be to honour the humility of Our Lord, in the communion to attract it into my heart, and by the co-operation to reproduce it in my conduct.

I place myself, then, carefully, in presence of my divine model;

I contemplate His interior sentiments before the infinite greatness of His Father, while bearing the shame of our sins; I listen to the teachings, by which He preaches humility to us; I follow Him for a moment throughout the mysteries in which He most annihilated Himself. This can be done rapidly.

I adore my infinitely great God in His abasements, I admire and praise His sublime annihilations, I thank Him for His humiliations and His example, I love Him for so much goodness, I rejoice in the glory which God the Father receives, and in the grace which comes to us in consequence, I compassionate the sufferings of our humiliated Lord. These various acts form the adoration, the primary duty of prayer.

There is next question of drawing into myself the interior sentiments and exterior life of humility which I have just adored in Our Lord. This is the communion, and it is accomplished chiefly by prayer. I shall need an ardent desire, so that I may open very wide the mouth of my soul, and a prayer, based upon a deep conviction, so as to receive into my heart not the body of Our Lord, but His interior dispositions.

I shall hunger for them and ask them as I ought, if I first understand that these dispositions are for me sovereignly desirable, and that I am in want of them. I shall make a prolonged consideration of my divine model, in order to engrave His features upon my mind and heart, in order to be smitten with esteem and love for Him; either by recalling, in general and by a simple view of faith, the motives which I have to imitate Him, or by leisurely running over in my mind these reasons one after another by a sort of examination, or, in fine, by striving to deepen my convictions by close and solid reasonings.

I may make such reflections as the following, or similar ones: Oh! my Jesus, how humility pleases me, when I contemplate it in Thee; Thou dost seek for humiliations with avidity, and dost communicate to them a surpassing virtue and sweetness; so that there is no longer anything in them which should repel me.

I should be ashamed to be proud, mere nothingness that I am, when my God makes Himself so small. Thou wouldst blush for Thy disciple, and our common Father would not recognize me for Thy brother, if I resemble Thee not in humility and humiliations. My pride would harmonise badly with Thy annihilations, and would inspire Thee with horror. It is not possible to be Thy friend, Thy intimate, if I have not Thy sentiments, &c., &c. And yet how far I am from all this!

These considerations suggest reflections upon one's own conduct; I examine my thoughts, words, and deeds to see in what I resemble my divine model, in what I differ from Him. This examination easily excites sorrow for having imitated him so ill in the past, shame for my miserable pride in the present, and a will to do better for the future.

These considerations and this examination will make me esteem, love and desire the humble dispositions of Our Lord. It is chiefly prayer that attracts them into my soul, it is by it that, properly speaking, the communion is effected.

I shall, therefore, dwell upon it with special insistence, striving to make my petition humble, confiding, ardent, and persevering; I shall pray and implore Our Lord to impart to me His dispositions; I shall place before Him the reasons which seem to me the most moving, and shall invoke in my favour the intercession of His blessed Mother and of the saints.

It now remains to transmit to my hands--i.e., to transmute into works, this spirit of Our Lord which I have just drawn into my soul. For sentiments, to be of any value, must lead to action. I take, therefore, the resolution to correspond with the lights and graces received in my prayer, by imitating Our Lord in such or such a practice of humility; this is the co-operation. I then terminate my prayer as before.

IV. SOME COUNSELS.

1) As we have already pointed out, it is as much an illusion to despise method as to be enslaved to it. Beginners, inexperienced in the ways of mental prayer, have need of a guide to lead them by the hand. When we have become familiar with the divine art of conversing with God, and our heart desires to expand more freely, a method might be an obstacle; it would especially embarrass us in the prayer of simplicity, and be an impossibility in mystical contemplation. We must, therefore, have the courage to follow it as long as it is of service, and the wisdom to dispense with it when it becomes an obstacle.

2) It is not necessary in the same meditation to go through all the acts of our method. Those which we have briefly indicated, and which we will now describe in detail, are sufficient to enable a soul with a turn for meditation, and who is not plunged in aridity, to occupy herself without much difficulty for hours in prayer, whereas the time assigned by our rule to each exercise is rather short.

Are you penetrated with a lively feeling of the divine presence in your preparation? Receive it as a grace, and take care not to pass on so long as it is doing you good. A consideration touches you and excites pious affections, leave other reflections aside so long as this one is nourishing your soul; a pious act, say of divine love, of contrition, of gratitude, attracts and occupies you; do not leave it to pass on to others; you have found, cease to go on seeking. Nevertheless, it is always to affections, petitions and resolutions we should more particularly apply ourselves, as being the principal end of prayer.

3) For a stronger reason there is no necessity to make the acts in the order marked out above. We had, of course, to describe them in their logical sequence; but, if a movement of grace urges you to adopt a different order, follow then the guidance of the Holy Ghost; the method is meant to aid and not to embarrass us.

St. Francis of Sales insists much on this advice: "Although, in the usual course of things, consideration ought to precede affections and resolutions, yet if the Holy Ghost grants you affections before consideration, you ought not to seek for consideration, since it is used only for the purpose of exciting the affections. In short, whenever affections present themselves to you, you should admit them and make room for them, whether they come to you before or after any consideration. And this I say, not only with regard to other affections, but also with respect to thanksgiving, oblation, and petition, which may be made amidst the considerations. But as to resolutions, they should be made after the affections and near the end of the whole meditation.''

4) Let us apply our powers energetically to prayer, our mind by a firm and sustained attention, our will by animated and energetic acts. There is a vast difference between the prayer to which we wholly devote ourselves, and that to which we apply ourselves only languidly.

But as we must fear the laziness which will go to no pains, so we must equally fly a too intense application, which oppresses the head, strains the nerves, fatigues the heart and chest, exhausts the strength, and may end by repelling us altogether from an exercise which has become too painful.

5) Prayer is more the work of the heart than of the head; it should, therefore, be simple, affective, and sincere. Let not the mind, then, weary itself in seeking for beautiful thoughts and sonorous phrases; we meditate not to prepare a finished sermon, nor to address God with fine rhetoric, but to nourish our soul with reflections which may enlighten and move us, and excite holy and generous resolutions; we make these reflections for ourselves alone, let them, then, be simple as well as pious.

In affections, likewise, we seek for the practice of virtue, and not for the pleasures of a refined egotism. Let us never confound our sensible feelings with our will, or mere emotion with devotion.

None of these acts need be made with a feverish ardour, nor in a tone of enthusiastic fervour. When protestations of friendship, gratitude, &c., are addressed to ourselves, the more simple and natural they are, the more they please us; the moment they appear forced, their sincerity becomes suspected.

Above all, our prayers should be the faithful echo of our interior dispositions; our affections should express the sentiments which reign every resolution should be a firm purpose of the will, and thus our whole soul will be upright and sincere before God.

Imagination, sensibility, emotions are by no means required, nor are they sufficient for this work. It is the will that makes the prayer. Though our heart be in desolation and coldness, and devoid of all feeling, yet, as long as our prayer proceeds from an upright and resolute will, it is pleasing to God, who beholds our interior dispositions.

6) Let us not prolong our prayer solely from the motive that it is consoling; this would be to seek ourselves rather than God. Away with vain complacence and spiritual gluttony! Let us receive sensible devotion with humility and detachment for the purpose of uniting ourselves more closely to God, and of being enabled to make for Him those sacrifices which we have hitherto refused Him.

Let us make use of it and not be its slaves. In order to hide it beneath the veil of humility, and to preserve our health against its excessive ardour, let us moderate, if necessary [as St. Teresa of Avila expressed it], “those emotions of the heart and those not uncommon movements of devotion, which tend to break out into external manifestations, and seem as if they would suffocate the soul;…Reason should hold the reins in order to guide these impetuous movements, because nature may have its share in them; and it is to be feared that there is a good deal of imperfection mingled with them, and that such movements are in great part the work of the senses, whatever is merely exterior ought to be carefully avoided." "Tears, although good, are not always perfect. There is ever more security in acts of humility, mortification, detachment, and the other virtues.''

Let us never imitate those [this is also taken from St. Teresa of Avila] “indiscreet persons, who through the grace of devotion have ruined themselves, because they wished to do more than they could, not weighing the measure of their own littleness, but following the affections of their heart rather than the judgment of reason."

7) On the other hand, let us not shorten our prayer solely because it is full of desolation, A duty in which we find no pleasure is none the less a duty. To please God, to do good to our own soul, is the end of prayer; if consolation is withheld even till we reach heaven, the reward will be only all the greater. Hence, let us not yield to weariness, disgust, murmuring or discouragement; but let us begin by examining ourselves.

Perhaps that fourfold purity, of which we spoke, has been covered with some dust; perhaps we have been obstinate in our own opinion or yielded to self-will, offended charity by some antipathy, or entertained some inordinate attachment, broken silence, or given way to dissipation, committed more petty faults than usual, or multiplied our irregularities.

The hand of God, as merciful as it is just, punishes our failings, and recalls us to our duty; let us adore with submission His fatherly severity, and not sulk with unrepenting pride. Perhaps God wishes merely to preserve us in detachment and humility, to test the solidity of our faith, to try the constancy of our devotion, the strength of our will, the disinterestedness of our service. Or perhaps this desolation is but the prelude to greater graces. However that may be, let us never doubt the loving heart of our Father, "Who chastises us because He loves us." Far from abandoning our prayer let us continue it with courage.

The soldier remains at his post in spite of danger and fatigue; the ploughman bends over his furrow despite the inclemency of the weather. There is, in fact, nothing less troublesome than this powerlessness of the mind and this desolation of heart, when the soul has the courage, either to suppress what may be their voluntary cause, or to embrace this cross with love, and to persevere in prayer with patient energy.

During long years, St. Teresa sought in vain for a little consolation in prayer. She persevered, however, and, as a reward, God inundated her soul with His favours, and raised her even to the heights of contemplation and of perfection. Our Lord deigned one day to say to her with an accent of the most tender affection: [As she wrote of what he said] "Be not afflicted, my daughter; in this life souls cannot always be in the same state; sometimes you will be fervent, sometimes without fervour; sometimes in peace, sometimes in trouble and temptations; but hope in me and fear nothing." God is very near the soul that generously does its duty in spite of dryness.

8) Our prayer being ended, all is not yet done. It should, moreover, embalm with its divine perfume the Work of God, our free time, and the manual work which may follow it. We must strive, therefore, to preserve during our other exercises the recollection, the pious thoughts, and holy affections we experienced in our prayer.

We are like a man who is carrying priceless liquor in a fragile glass vessel; he will look now to his feet lest he make a false step, now to the glass lest it be tilted to one side and be spilt. No doubt we must pass from prayer to action, but, while abandoning ourselves for God and under His eyes to our various occupations, we must also "keep an eye upon our heart, that the liquor of holy prayer may be spilt as little as possible," [according to St. Francis de Sales] through our natural activity, dissipation, routine, stress of business, or even the artifices of the demon.

9). [Fr. Lehodey quotes from St. Francis de Sales here as well:]“You must especially bear in mind, after your meditation, the resolutions you have made in order to put them in practice that very day. This is the great fruit of meditation, without which it is very often . . . almost useless. . . . You must then endeavour by every means to put them in practice, and to seek every occasion, great or small, of doing so. For instance, if I have resolved to win over by gentleness the minds of those who offend me, I will seek on this very day an opportunity of meeting them, and will kindly salute them;" I will render them some little service, I will speak well of them, if permitted to speak; I will pray for them and carefully avoid causing them any pain.

FROM OUR BOOK AND GIFT STORE

OR CAFE PRESS STORE!

Return from Dom. Lehodey on Mental Prayer

to Mental Prayer Page